The good news, at least from my perspective, about Stanley Kubrick’s highly lauded 1987 war flick Full Metal Jacket, is that the second act isn’t as wan as I recall. It is an oddly shaped film, sort of like two episodes of a TV show, stitched together to make a pilot. (“We’ve gotta have a boffo opening! Make the first episode two hours long!”) The bad news (again from my perspective) is that the first act is even less believable than I recalled. It’s a brilliant bit of filmmaking, and very compelling, no doubt. But it seems to fundamentally misunderstand human nature.

Fine acting. But the subsequent “character development” is incoherent.

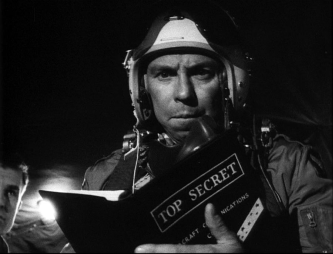

I mentioned the challenges of ranking Kubrick film in the Dr. Strangelove entry, although since then I have observed a curious thing about rankings: The aggregates tend to put Dr. Strangelove at the top and FMJ in the top half, but individuals who make their own lists seem to favor 2001 and respect FMJ much less. This is probably due to this 2-act narrative. (A critic is more likely to think that maybe, when a guy like Kubrick does something unusual like this, it’s worth more consideration than, say, some hack fumbling with a stupid premise. A regular moviegoer is more likely to say “I didn’t like it. It was weird.”)

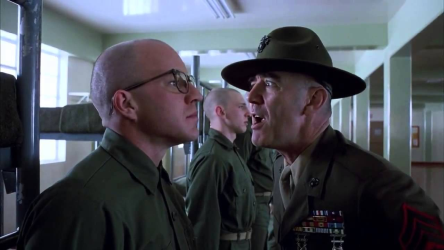

But let’s look at the first act first. This is the narrative that launched R. Lee Ermey’s career, and he is spectacular in it. He is hilariously horrifying in his abuse of the soldiers, politically incorrect in extremis—and in a way that was shocking even way back in 1987, and would be unthinkable today. Part of the disconnected feeling of the second act, in fact, probably stems from the fact that his behavior does, in fact, seem to be completely arbitrary. That is, at no point are we ever prompted to recall the training which, in the second act would have been pretty critical to survival. But that’s not really the problem with the first act. The problem with the first act is Vincent D’Onofrio—or more rather, Kubrick’s relationship with “Private Pyle”.

“Only two things come out of Texas, Private Joker: Steers and people who haven’t seen FULL METAL JACKET!”

This is, necessarily, going to be spoiler territory.

The first act has its own arc, as our hero, Private Joker makes his way through a hellish Physical Training, while he and his fellow recruits are being tortured because of the mentally deficient Pyle. And, here’s the problem: Pyle is distinctly represented as brain injured. Not just a little irresponsible or lazy, but genuinely impaired mentally. He has trouble making his bed or tying his shoe laces to military standards. (This guy wouldn’t get anywhere near today’s corps, I gotta believe, but I don’t know that such things weren’t possible back in the ’60s.)

Where it all falls apart is when the soldiers “fix” Pyle by beating him with soap wrapped in pillow cases. All of a sudden, Pyle is a lean, mean fighting machine. The Boy pointed out that that might not have been the case, and that that wasn’t what was intended, only that the movie showed the areas where he excelled afterwards (especially marksmanship). But this is what we see: Kinda friendly dope beaten into a murderous efficiency, literally.

But, of course, brain injuries don’t work that way. Volition doesn’t enter into it when a brain-injured person can’t figure out right from left, or doesn’t know what the responsible, correct action is. The idea that it a mental handicap can be remedied that way is what led to the torturous treatment of “morons”, “idiots”, “the retarded” throughout the 20th century and (of course) earlier.

What I think, though, is that Kubrick wanted to show the brutality of PT, and the warping of an innocent but dumb kid fit the narrative. And he went too far. In real life, if you beat a kid like that, they’ll have a nervous breakdown, not rise up in ability level.

Yeah. No.

And the subsequent murder of the Drill Instruction by Pyle is completely unsupported, except through this magical personality change achieved through pummeling.

It’s funny, though: When I think of “directors with a strong understanding of human nature,” I don’t really think of Kubrick. I mean, if you’re recalling characters in Kubrick films, you’re thinking of what are, essentially, caricatures. Jack and Wendy Torrance, Alex from A Clockwork Orange (1971), the entire cast of Strangelove. Hell, what do people remember about 2001? The psychotic computer. (I haven’t even seen this one, and that’s what I remember.) Maybe Barry Lyndon and Spartacus are different, or maybe Kubrick’s wheelhouse wasn’t the traditional character arc found in a three act narrative.

Food for thought.

And this leads us to the second act, and maybe why I liked it better this time around. The second act is a series of things that happen, in sequence, that lead logically one to the next, but which don’t, particularly reveal character. In fact, I think that a number of the critical objections to this film are based around it’s “morally muddled message” (as I think Ebert put it). Our hero, Joker, is perhaps meant to be seen a bit more like Alex than a typical John Wayne character: He’s not a hero. He’s some guy who sort of trusts the institutions of the country enough to believe his presence will be a good thing.

“We had to destroy the village in order to save the rest of the villages from being destroyed by the Communists.” Not as catchy but as it turns out, true.

As such, his final action, the climax of the film, where he kills a young girl who has sniped several of his best friends, is rather anticlimactic. He does it; he moves on. He’s surrounded by battle-hardened veterans who have a problem killing this little girl, and he does it with only a little goading, and no subsequent remorse.

Maybe what Kubrick is getting at here is that Joker isn’t the person in question, the audience is. This maps pretty well with Clockwork Orange where we are inclined to root for Alex, not because he isn’t the embodiment of evil, but because there is something worse than that: Brutal inhumanity done to suppress the individual’s free will. Not that Joker is evil, exactly, but his smile isn’t exactly unlike Alex’s as he heads off to the next location where he will have to kill some more.

The kids liked it. The Flower loves “These Boots Are Made For Walking,” so I think she sort of recalls this as “The movie with the good music.” She also likes some Ermey (as do we all, except for The Engima, who refers to his program “Mail Call” as “History Shout”). I think The Boy also found the second act a little more palatable than he had previously.

I don’t know. I’m not sure if it’s “muddled” as Ebert said, or if it’s just war that’s muddled, and that’s what’s being shown. But it is, of course, as all Kubrick films, a technical masterpiece.

She did point out that the girl in question was not actually wearing boots, however.