And that’s what you get for bombing Pearl Harbor!

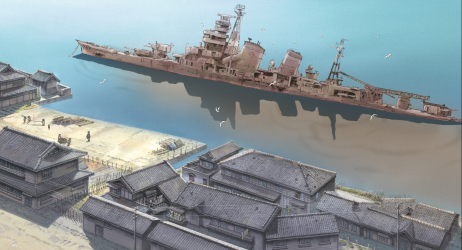

Representative of the mighty Imperial Navy, now at the bottom of the ocean floor.

I kid the Japanese! I kid because I love! And also because we pretty much wrecked up their country after WWII. Not the bombs, but the liberalization. It’s almost inconceivable to imagine Japan achieving their current childless, robot-loving, otaku state without it. (Aw, dammit, I just used this same Pearl Harbor joke for Grave of the Firelies. I must think it’s really funny.)

But this movie, In This Corner of the World, takes place before all that, when a young Japanese girl did all she could for the war effort and pretty much resigned herself to marrying whomever and going off to live with him and his family.

I’m not gonna speculate on why it is that middle-aged (and older) Japanese men seem to be preoccupied with the fates of young girls (Studio Ghibli, prominently), except that maybe that’s who goes to the movies in Japan: young girls (and maybe men who wish they were young girls—but I’m not gonna speculate, I tell ya!). I will say that they seem to be pretty good at it, however.

Young love. (This is actually one of the least “kawaii” moments, in terms of the art.)

This is the story of Suzu, who grows up during the Japanese empire’s brutal expansion and of the ’30s (and the subsequent denouement of the ’40s). It is, fortunately, not a retelling of Grave of the Fireflies. (Not because Fireflies isn’t brilliant, but because one movie about children starving to death is enough.) When we meet Suzu, she is a pubescent girl who delights in telling her littler sister stories, which she draws pictures for. There’s a boy she likes, kind of an oddball, whose father is serving aboard a naval ship.

We flash forward a few years and the war is really heating up. It’s turning against the Japanese, though this is only subtly hinted at, because of course the Japanese government presented a constant “victory is at hand” message, and even suggesting otherwise was treason. But the interesting thing is that Suzu never really questions it. She isn’t happy about the privation (not nearly as severe as Fireflies, obviously) but she’s happy to contribute to the effort. She’s a good Japanese woman.

A lot of very pretty landscapes shots to be admired.

She moves away from home to marry a stranger—her path crosses with the oddball boy a number of times, but he goes off to war, and she ends up with a very nice man who is unfit for service. There’s an interesting moment where they send her home, and she acts and seems to believe at some level that her marriage (about 18 months long at this point) never happened. This actually confused me until the segment was over and she had returned. (I think, partly, the kawaii style of the character drawings was such that it made passage of time a little bit hard to distinguish.)

In another interesting vignette, the oddball boy comes back and, as a warrior, he can basically make a claim against her. Her husband actually pushes her into his arms (not happily but with a sense of duty) and Suzu and the soldier spend the night together. However, Suzu has realized that she really loves her husband, and her childhood friend has no interest in forcing her into anything, only returning to see her because he thought her (nearly random seeming arranged marriage) was an unhappy one he could rescue her from. This is a nice story though it takes an aggressive amount of tamping-down-on-the-imagination to not figure how this sort of arrangement usually played out. (Suzu is rather naive and runs into a destitute girl she had encountered years earlier in a red-light district without clueing in.)

Interestingly, Suzu starts out just outside of Hiroshima but her husband lives further away. When the bomb hits, she’s not there to witness it, but instead goes back later hunting for friends and family. This is poignant in a way that being there for the bombs would not have been.

This is when Suzu finds out Japan lost.

Also interesting is that Suzu’s despair comes from losing the war. You don’t see that a lot, but of course it makes sense. The hardship the Japanese (and even German and Italian) people endured made sense in the context of some larger glory promised to them by the Japanese elite. Something about a run-of-the-mill, sweetheart girl like Suzu expressing imperialist sentiments brought that home in a way that, e.g., Letters from Iwo Jima did not precisely.

There is a shocking and unforgettable moment with a little girl and a land mine, too.

I don’t know, folks: The Japanese own this kind of animation as a vehicle for telling non-kid stories. I imagine this to be in the “young adult” category as most of the anime/manga stuff is. But they really do kick ass and bend the genre in ways we don’t see in America. The kids loved it—but so did I!

Was it just a dream?

One thought on “In This Corner Of The World”