Try this on for size: While 12 Angry Men is one of the greatest films ever made, if you think it’s socially important, you should feel exactly the same way if, in the end, the freed defendant goes and kills everyone who testified against him at the trial.

You know Lumet picked this guy ’cause he looks harmless.

Greg Gutfeld thinks this movie was significant in turning the opinions of Americans leftward, against each other. A mostly diffident group of men—they don’t start out angry, except maybe for Lee J. Cobb—are about to put away a poor, unfortunate urban youth whose unfortunateness unfortunately extends to an unfortunate amount of circumstantial evidence which, unfortunately, is against him.

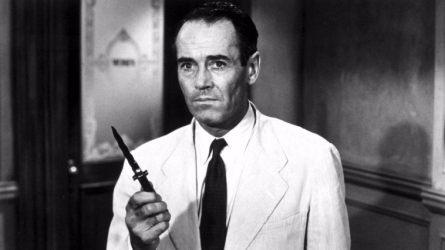

All around American good guy, Henry Ford, plays Juror #8, the lone holdout in sending our defendant to the chair. Over 90 or so minutes, Fonda grinds them down with “just asking questions” and taking apart the prosecuting case while not so subtly making the point that not everyone gets a fair shake in our legal system. But, like I said, if you believe that, the defendant going on a killing spree after being freed should not change your opinion.

Our system is not just about presumed innocence, but about holding back the awesome power of the state when it comes to locking people up.

Even when it’s THOSE people. And “you know what THOSE PEOPLE are like”, as Ed Begley intones at one point, speaking perhaps of, I don’t know, Italians? The Flower noted this at a later point, that no specific race or identifying slur was mentioned—she figures he meant Catholics. I pointed out that that was most certainly deliberate and completely unrealistic. (What racist doesn’t enjoy a good slur?)

He makes a good point. I mean, after all Jack Klugman is One Of Them.

But politics and social commentary aside, this is a great movie, deservedly listed as one of the best of all time (#5 on the ever dubious IMDB top-250). Sidney Lumet’s first film, which might’ve been shot in one take like the stage play it feels like, but instead used hundreds of takes, masterful blocking, and a bunch of American greats doing their greatest. I think I can name them in order, one through twelve, just from memory: Martin Balsam, John Fiedler, Lee J. Cobb, E. G. Marshall, Jack Klugman, Edward Binns, Jack Warden, Henry Fonda, Joseph Sweeney, Ed Begley Sr., George Voscovec, Robert Webber.

OK, I had to cheat for Edward Binns and George Voscovec, but I remember the characters they played very well—front-line salesman (versus Webber’s Ad Man) and noble immigrant—which is more important. All of them classic character actors who worked to the end of their days, if I’m not mistaken. And of course Fonda.

Shot on a modest budget—The Wayward Bus was shot in the same year on a $1.5M budget versus this film’s $350K—and ultimately disappointing at the box office, perhaps due to its “small screen” feel, being in black-and-white and taking place in a tiny room, it really pays to see this on the big screen. This is high drama, melodrama none would dare call it (except me), and its overwrought nature is testament to its greatness.

Twelve ang—no, wait, ten! Ten angry men!

I mean, seriously: Nobody’s really gonna chew the scenery like that in a jury room. It ain’t realistic or natural. I only point this out because a lot of the critics who love this film are in love with low-key anti-dramatic performances. Screenwriter Reginald Rose may have been inspired by a real stint of jury duty he did, but I don’t see people getting this worked up back in a jury room in 1957—that’s why you went to the movies.

Come to think of it, it’s more like an Internet message board.

The interpersonal dynamics are great. The way people ally and break and form new alliances and coalesce around what’s popular, etc., and little of it having anything to do with the received facts. You end up rooting for all the characters at one point or another, even No. 3, which is a sign of greatness.

Unsung hero?

Obviously it’s tilted toward the notion the defendant is innocent. That’s really the only cheat. The screenplay never gives you much room to doubt that the guy is innocent, and being railroaded. Fonda is not as convincing—perhaps just because of who he is, iconically—as someone who would defend a murderer. The audience is given to believe that he’s right, not that he’s merely defending the concept of “reasonable doubt”. That may also be due to the iconic nature of the film.

There’s a wicked, brilliant Russian version of the film, which in some ways I enjoy more than this, because it turns the whole concept on its ear. The corrupt society this movie imagines can’t even hold a candle to an actually corrupt one.

Spare, effective score by Kenyon Hopkins, who would go on to do the score for The Hustler but who probably imprinted himself on America’s brain most effectively through his work on ’70s TV shows like “The Odd Couple”, “The Brady Bunch” and “Mission: Impossible”.

Ultimately, though, it’s the blocking and lighting that make this great and something you can watch again and again. Director of Photography Boris Kaufman had won an Oscar for On The Waterfront, but I can’t help feeling he was on a short leash here. Lumet’s cinematic style would be hammered in over the next 50 years. It’s a good collaboration here.

This was on a double-feature with Witness for the Prosecution and would start the series of five films we would see in a row—the last three being Guys and Dolls, Casablanca and West Side Story—after which The Flower would declare we had seen all the good films.

Sadly, Henry Fonda’s campaign to personally stab everyone who bought a ticket did not help the box office.

4 thoughts on “12 Angry Men (1957)”