It was probably the whiff of family dysfunction that put me off The Royal Tenenbaums when it first came out. It is not at all that I can’t enjoy a good family dysfunction movie, as you can see by clicking on each of those words individually—and I assure you that those were just the first four movies that came up when I searched for family dysfunction films—but that a bad family dysfunction movie is second only to bad comedies and rape-heavy-torture-porn-horror in terms of unpleasant ways to spend an afternoon. This was the era of You Can Count On Me, In America, The Hours and a host of other family dramas that (good or bad) were not necessarily something I was in the mood for.

This is the only family dysfunction film featuring Dalmation mice, however.

But the thing about Wes Anderson films is that even when they deal with serious things—and all of them do—they use a light touch. We are all in this modern, soft world, sort of absurd characters, hyper-ventilating over minor offenses, while generally managing to rise to the occasion, to overcome the liabilities, to actually make something cool out of life. And The Royal Tenenbaums is a strong vehicle for that message.

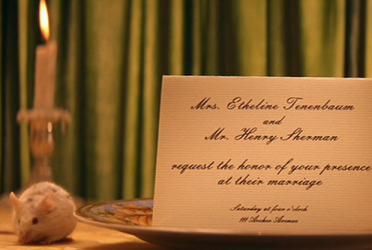

In it, Gene Hackman, in one of his last roles, plays Royal Tenenbaum, a man completely unable to focus on his family. I don’t know quite else how to describe it. He’s unfaithful, sure. He can’t introduce his adopted daughter Margot (played by Gwyneth Paltrow) without pointing out every single time that she’s adopted. And eventually he just goes away, leaving his eccentric but driven wife Etheline (Anjelica Huston) to raise the children. The children themselves are also eccentric, to say the least, driving toward their own sorts of success in their own weird ways.

We meet the kids as kids, and then flash forward about 20 years. Margot has written one book, well-received, but has basically caved in on herself, shacking up with a much older English professor (Bill Murray). Chas (Ben Stiller) is successful but has been widowed about a year before the movie’s current time, and has responded by being the prototype, archetype and apotheosis of a “helicopter parent”. Richie (Luke Wilson) was a fantastically successful tennis player—now traveling the world in obscurity because he flat out gave up at a single match. (The reasons for which are ultimately explained.) Added to the mix is Eli (Owen Wilson), the next-door neighbor kid who ends up being unofficially adopted by Etheline, and a good reminder that as weird as the Tenenbaums had it, it was still much better than many.

Love this game closet.

The movie begins when Royal returns, seeking to reunite with his family, because he is dying of cancer.

This could be really bad. And if you don’t like Wes Anderson, this isn’t the movie that’s going to win you over, most likely. But the thing in evidence here is this: He respects his characters, even at their most ridiculous and even at their most awful. All of the kids have talent and ability—well, maybe not Eli, who seems to just be an opportunistic drug addict—and they are more or less able. As Royal rebuilds the bonds with his family (and tries scuttling Etheline’s burgeoning romance with her accountant, played by Danny Glover) the questions we are faced with are universal: What does family mean? Do we extend help to our family members even when they don’t deserve it? And if we can build bridges when things are desperate, why can’t we just build them whenever? Why does it have to be desperation?

And, when we’ve extended the mantle of family to another, is that a permanent, irrevocable thing? This movie seems to answer in the affirmative, as the roguish Eli, in his continuous evasion of the Tenenbaums’ attempts to get him off drugs, nearly kills Chas’ son. By the end, you’re less shocked by Royal’s uproarious laughter at a play based on him, written by Margot, and showing him to be callous toward her, and more just shrugging: Yeah, that’s who he is. He’s not even being mean. He just doesn’t comprehend the hurt.

You probably wouldn’t want to sit next to him during the show, of course.

You could say this movie (and all them, really) is about tolerance. Family is a microcosm of society, and first and foremost, one must tolerate others. No matter how awful they seem. The nice thing about this movie is that you can see and empathize with the different characters. They all have good traits in the mix.

The kids all liked it. I did, too, quite a bit, and more than I expected. I suspect if I had seen it in 2001, I would be saying I liked it more this time—because that was true of all five films.

And look at that BLOCKING!