We followed up our viewing of the original Phantasm with the fifth movie in the series, called Ravager, I think, because you can capitalize the “V”. RaVager, ’cause it’s the fifth in the series, see? Like the fourth one was OblIVion, with a capital “IV”. Anyway.

This naming scheme gets to be a problem when you get to VII.

I actually haven’t seen a Phantasm sequel since #2 came out in 1988, and while I enjoyed it a great deal, it obviously isn’t as iconic as the original. (How could it be?) I’ve seen bits and pieces of 3 and 4, and it’s kind of been fascinating and fun to see the series gradually shift into a post-apocalyptic survival horror, where Reggie and Mike (and sometimes Jody) go mano a mano with The Tall Man, somehow thwarting his evil plans without actually ever thwarting his evil plans. (In other words, where they seem to come out the winners to some extent, and to the degree that the Tall Man seems to find them mildly irritating, the world still slips into an abyss of undead horror.) This process started in the second movie, and it’s full blown here.

Sorta.

It’s a beautiful day in the apocalypse.

As a fitting conclusion to the series, our story begins with Reggie wandering in the desert—

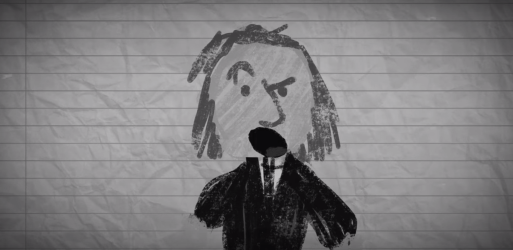

Wait, let me back up a step: Given that a lot of people probably haven’t seen 2, 3 and 4, and maybe not even 1, the movie actually started with an educational short on what happened in the previous movies, called “Phantasm and You”. This was very cute.

They couldn’t use scenes from Phantasm II, so they…improvised.

The Boy and I couldn’t help but notice that while Boyhood took twelve years to make, the Phantasm saga took forty years to make, if it is indeed true that the initial production began in 1976 (and took over two years) and also that five was just finished. And while this is a humorous observation, perhaps, it does show on-screen in the movie’s best parts: Reggie and Mike have a lot of chemistry that feels very natural. (Mike was just a kid when the first movie started shooting, and half-a-lifetime of experience hasn’t hurt his emotional range.) Bill Hornbury doesn’t show up until the end, but he doesn’t phone it in in his brief scenes. Angus Scrimm, who died in January of this year, also manages to pull his weight, despite being in his late ’80s.

Director David Hartman (best known for directing animated kidvid like “Tigger and Pooh”, “Transfomers” and so on) wisely lets these guys do their thing, together and singly, including an amusing segment where Reggie tries to work his seductive powers on the new girl—I think every girl in the series is either The Tall Man or one of his minions or quickly killed by them, so abstinence might have been the most humane course, really—and, well, he’s a lot older now.

The ’71 ‘cuda, practically a baby when the first movie was shot, is now 45!

Hartman opts to split the movie in two parts: Half with Reggie in an old folks home/hospital, half with Reggie in the post-Apocalyptic world. The split allows for a lot of the dramatic bits that work (including Angus Scrimm with a walker, and both he and Reggie delivering lines from hospital beds), but is also, at times, alienating. It’s a difficult thing to do well, and often violates the “stay in the phone booth with the gorilla” rule (as I’ve written previously). It does pull together by the end, though, so you don’t feel like you’re just being jerked around. (Too, Hartman may not have had a lot of choice, given that this film was produced over many years, originally conceived as a web series.)

The post-apocalyptic parts are good but really show the limitations of the budget. The original movie used a guy throwing the silver spheres and then playing the film backwards to get the effect of them flying. They’re all CGI here but the old trickery was actually a lot better. It’s the level of CGI where you go, “Oh, this is CGI.” There’s some CGI trickery used with the “Lady in Lavender” (Kathy Lester), too, but let’s give her a hand for looking like that 40 years later.

And, once again, they made her bring her own dress and got blood all over it!

When you get down to it, though, the biggest weakness here is that it’s a fan film, even with Coscarelli’s blessing on it and some writing credits. However iconic the most memorable aspects of the original film were—and one could compare it to the Star Wars prequels and their similar flaws—that doesn’t mean those images can support an entire universe. The universe teased by the original film, really, could perhaps have found its closest parallel in Pitch Black and its subsequent sequel Chronicles of Riddick. But I almost can’t imagine the world where that would make any kind of economic sense.

There are many cinematic universes out there: None of them are horror. (Universal, allegedly, is working on one but of course they’re going back to the ’30s for it.)

Anyway, we did like it. There were some clever ideas and good bits in-between the genuine, deep emotion of those scenes. But it’s definitely by a fan, for the fans.

R.I.P. Angus. The Tall Man Will Live On.